Last week, science did what science does best: it resisted the story that’s most exciting, or most comforting, in favor of the one that’s true.

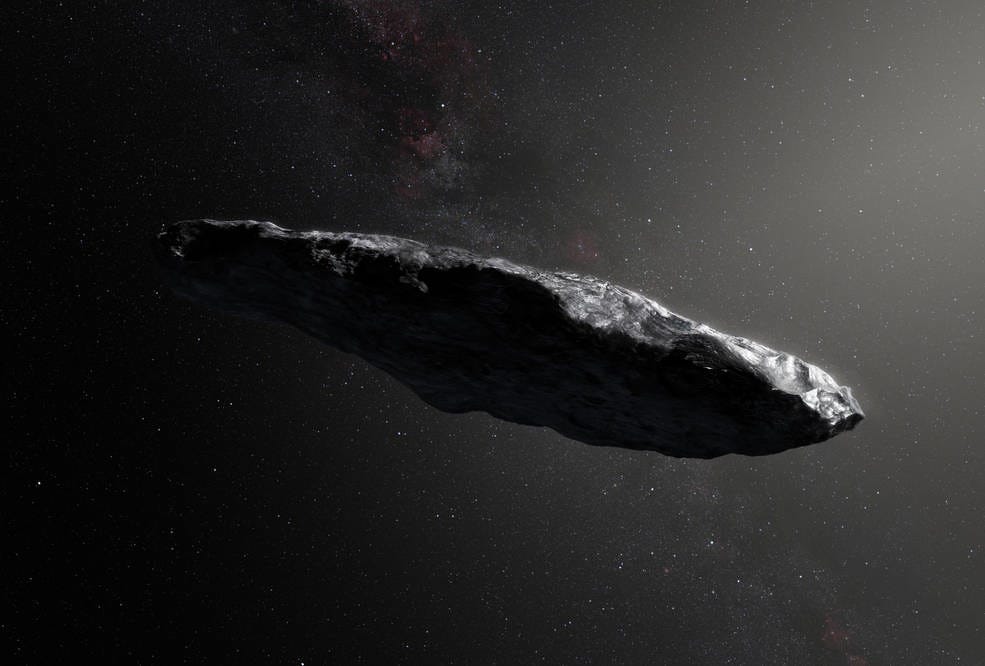

In late 2017, an interstellar object — dubbed Oumuamua, Hawaiian for “scout” — passed through our solar system and left the scientific community baffled by its bizarre shape and behavior. Immediately, there were murmurs about Oumuamua being an alien spacecraft. Among those who championed the theory was a veritable high priest in astrophysics, Avi Loeb, the longest-serving Chair of Harvard’s Department of Astronomy.

If proven true, that Oumuamua is alien and intelligent life exists beyond Earth, it would be the greatest discovery in human history — science’s Holy Grail.

So what did scientists do with this opportunity? They bowed their heads and worked, for three years, to produce an explanation. Last week, they put forth their best explanation to date. It will bore you to death. Oumuamua is most likely a chunk of ice.

Indeed, science is heartbreaking work of staggering discipline. You thought the kids who delayed gratification in the Stanford marshmallow experiment were impressive? Check out the astronomers who worked Oumuamua.

But let’s not go crying over debunked UFOs. This is a story of triumph. In the supposed drab, mechanistic march of the scientific method, there is stirring beauty. In its humble discipline, there are timeless lessons and real spiritual grace.

A typical criticism of science, from the perspective of a person scanning the spiritual marketplace, is that it depicts a disenchanted world, a meaningless physical tangle where “dust to dust” amounts to a pile of dust. This argument is compelling at first blush — it certainly feels true sometimes, like when a mother’s love is described as oxytocin — but it doesn’t hold up.

One way science is deemed disenchanting is that its origin stories are porous and uncomforting. Let’s examine that.

Here’s a spiritual vitamin I often take: I close my eyes and imagine a tiger’s face emerging from the absolute black of space. I find tigers to be one of the great marvels of Earth. Every time I see a tiger’s face, I’m stunned that such a thing has manifest — in the drama of its contrast and the stillness of its symmetry, I’m tempted to say our whole story is contained. Tigers humble and mystify me, they make me grateful to be alive, they leave me awash in awe.

Now, there are two leading explanations for why tigers exist. One: God made them. Two: They evolved over billions of years from an inciting microbial lifeform.

Based on what this animal evokes in me when I imagine its emergence — where once there was nothing, now there is this! — does one of these explanations belong in a spiritual category while the other does not? Or are they just different brands of magic? Is the miracle of a tiger bound to the mechanics of its emergence, or are we moved too just by the fact it exists?

Another way science supposedly disappoints us is by failing to deliver inspired explanations of underlying causes. Consider psychogenic shivers — what the French call frisson, and you may know as emotive tingles down your spine. These involuntary physiological reactions frequently occur as part of an emotional response to a narrative you encounter; for example, you may feel frisson while watching a movie in which a heroic character experiences a devastating loss.

Imagine two explanations for such an instance of frisson. One: It’s a whoosh of breath blown down your spine by a guardian spirit, as a way for the spirit to reinforce in you the value of empathy. Two: It’s an evolved trigger in your biological circuitry, as a way for nature to reinforce in you the value of empathy.

If the former proved true, we would say people guided by spirits learn to love each other and cooperate to build a better world. If the latter proved true, we would say social animals developed bodies that speak in resonant shivers, so they may learn to love each other and cooperate to build a better world.

Is that second explanation really so dreary and disenchanted? Is it going to leave anyone feeling hopeless and trapped in the apparent meaningless charade of nature? If you think so, perhaps it’s an issue of dosage — help yourself to some more frisson.

Put aside for a moment the question of whether science sufficiently charms us. What’s more worthy of our attention is how science embodies one of our most formative, life-sustaining values: humility. By this measure, with respect to existential mysteries, science is without rival on the ideological landscape. Remember, science does not claim the absences of God, the afterlife, or supernatural laws and realms. It only says, “We don’t know.” In that restraint, there is deep, abiding power.

Many ideologies want to end the discussion, or at least stifle parts of it. This is where a definitive separation occurs, in the way each ideology meets mystery. After all, mystery is the dark energy that drives us, not some ancient, all-encompassing explanation. The most important story is the one right before our eyes; not one located in unverified realms, with absent main characters, depicting a cosmos suspiciously small and shepherded. The story destined to unite us is the story we write as we go, huddled together in the dark, connected through resilience and imagination, carrying our torch of consciousness out of the seas and into the stars.

We love mystery, and all its attendant seeking. Any bee, tree or rock can kick back and live beneath questions. We’re built for more. Our biggest questions have remained with us, unanswered, since the emergence of our species. They are as inherent to our experience as opposable thumbs. And it’s precisely our striving in response to them that animates us in the ways we cherish most, through art, science, civics and philosophy.

With respect to these big questions, a person has three options: ignore them, believe they’ve been answered, or live inside them.

These modes track reliably with belief systems, but they aren’t codependent. There are atheists who believe the questions are answered and people of faith who live in the questions. Nor are these hardened archetypes — they’re more like attitudes we toggle between, depending on the variables.

When you ignore the big questions, you’re a biological mass set on autopilot, a sequence of base impulses. Few make a life of this, but many try. You will often find them on reality TV.

When you believe the questions are answered, you’re typically working from a culturally constructed script. You have a story that guides you. Even when the story doesn’t provide a clear answer, there’s a valve to relieve the pressure; usually something like, “I don’t know, but God does and I trust his plan.”

When you live in the questions, you are undeterred by the absence of answers. Your journey has a crucial added dimension — openness. In places where others put answers, you leave blank space, and yes, it’s just as sacred. This mode may not be the most comfortable, but it represents the best of the human animal, its highest setting. Anyone can default to mindless impulse. Anyone can seek shelter in a story and suspend the search. But to stand at the edge of darkness and hold out an open hand. What a thing.

You don’t need to believe anything to be spiritual. There’s no leap to take. Just be open. If you’re unsure, undecided, or on the hunt, you’ve already made it. You’re a scientist. Want to enjoy the ride? Make peace with mystery. Embrace it, fall in love with it. Go to it frequently, let it be a shrine you bow before to feel small and reverent.

To be humble in the face of mystery is to give the gift of greater enlightenment to every generation yet to come. In this way, we pay forward our debts along the continuum of human knowledge, connecting to each other across our collective past and future. If anything is spiritual, that is spiritual; that is self-transcendence and devotion to a greater good.

In the spiritual person, what do we expect to see? Humility. Devotion. A sense of meaning. A sense of connection. Perhaps faith.

In the scientist, what do we find? A person humbled by mysteries a thousand years out of reach. A person connected to the continuum of human knowledge. A person faithful to the scientific method as a source of truth.

No congregation of scientists may ever provide a spectacle as stunning as a hundred thousand Muslims in Mecca, bowing in unison. But their devotion is no less worthy of respect. They too move as one rhythmic body, millions of curious people bowing their heads into data of the observed world, and each morning, beginning again, returning to the work with a simple mantra: I don’t know, but I’m trying to see.

I think Einstein describes that state of mystery as the “cosmic religious feeling”

Wow, that was beautiful. And I do think about the Stanford marshmallow experiment pretty often. I think I’ve heard it said, maybe by Einstein, if you go deep enough into science, it becomes spiritual. Most people aren’t scientists so they don’t understand what that’s like. They understand science from all the *knowns* it provides—the things that make exploration unnecessary. And science is predicated on theories, which require a belief that something might be true. When you’re navigating that domain, there can be no other term for it because it’s unknown, so we just say “spiritual”... but, you’re right, science is just one way to interact with that.